I turned forty-one. Not the milestone celebration I had last year, singing my heart out with loved ones in a sake bar, but a quiet, soulful Sunday recovering from jetlag and the “spring forward” time change. I woke up with an urge to jump into the lake (in a happy way!), despite the fact my birthday falls inarguably in the lion’s end of March.

Throughout the winter, a group of brave swimmers caught my attention on Saturday walks near the beach. I noted the daring tuque+swimsuit combo from the recesses of my hood; vivacious laughter leading as they jogged from the shoreline to some sort of sauna set up by the road. I love a good thermal spa; but Lake Ontario, which I’ve begun to think of as a sea, seemed an aggressive masseuse, judging by the brightness of their pinked limbs and noses. By my birthday, the winter freeze (and my curiosity) had thawed enough that the idea of a cold plunge felt exhilarating.

It helped that we had just spent a week in Barcelona (hence the jetlag), and dodged the tail end of the snow. A beautiful place by all reports, something expansive relayed in the looks and tones of those who have been. Although I’d been wanting to visit for over a decade, I don’t think I could have gone any sooner, or younger. I needed to visit on the cusp of forty-one, at this time of my life when I have been unfurling like a moth. A city of artists, of architecture, of spiraling, scintillating, boundless exploration. It would not have hit me as hard, stayed with me as deeply if I had visited in my previous life, the one in which I could not imagine myself one of them – an artist.

The difference in me at forty-one to forty is subtle but profound. I liken it to the single grey hair I’ve sprouted and feel strangely maternal towards. Last year, having freshly quit my job, I wore a mask of relief and resolve. Despite knowing – and preaching – the rightness of my decision to leave healthcare, I felt as if I were merely on hold, a convalescent managing the burnout that had left me barely able to walk. Throughout the year I’d see job postings, and tell myself the time I’d taken off to date was sufficient. Just apply, and wouldn’t that be a tidy thing to tell folks later? Just kidding, I’m back. I’ve still got all my legs and caterpillar bits. Something that could hide inside the phrase, it was all just a dream.

But the current of the truth was there, below the surface of my days. I was afraid to acknowledge it, and covered it up with projects and grand ideas. I would create a business. I would write every day, two hours a day – clinician turned equity specialist turned published author, a six-month hiatus all that was needed to launch my next success story. I thought about going back to clinical work, with encouragement from old colleagues and potential clients. There were things I thought I’d be good at, great at. But it took all those garden paths to realize that what I wanted to do – what I, in my soul, needed to do – was write.

What can one change in a year? I can’t tell you that writing has been my priority, even as I have recognized it as a calling. Despite my restlessness, this year was dedicated to healing the house that carries me. My bones, tendons, and hormones were the foremost state of affairs. By the time I finally committed to leave my work, I was in such intense pain that I had lost mobility in my hands, was unable to carry my toddler up and down stairs, and woke up hobbling as my joints screamed with inflammation. I needed rest. My nervous system, keyed up from decades of overwork, protested this change of pace; as much as I tried to relax, it grasped and leaped and clung to new opportunities. It filled the void so necessary for my recovery with schemes of reinvention.

It was a year in which I learned that writing a novel doesn’t happen in two-hour shifts at a computer each day. At least, it doesn’t for me. On encouragement from a friend, I was assessed and diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD). The validation I feel that my brain operates in a functionally different way has helped me relax. It allowed me a new framework of compassion for myself, and I look back on my years of striving and see that I was held together with self-criticism, anxiety, perfectionism and shame. I lived an entire life on the knife’s edge of impostor syndrome. It is no wonder that a breakdown was fated for me.

A year of rest and integration. Despite not meeting my self-imposed requirement of two hours daily writing, I surprised myself by attending yoga classes nearly every day. My practice has evolved over fifteen years, especially during my yoga teacher training (completed with a torn hamstring and all the gifts of a global pandemic). It has come to invert all the typical elements of pace and sequencing into a deeply intuitive moving meditation, and over this past year has become a sacred personal therapy. I found an acupuncturist who sees my pain, who has led me deeper into healing than I’ve experienced in decades of seeking help. I discovered the “thermal cycle” on a visit to a nearby spa, and experienced the aching, tingling benefit of cold water in my arthritic joints. It was this discovery that encouraged me to find out more about those giddy dippers defying winter’s grip.

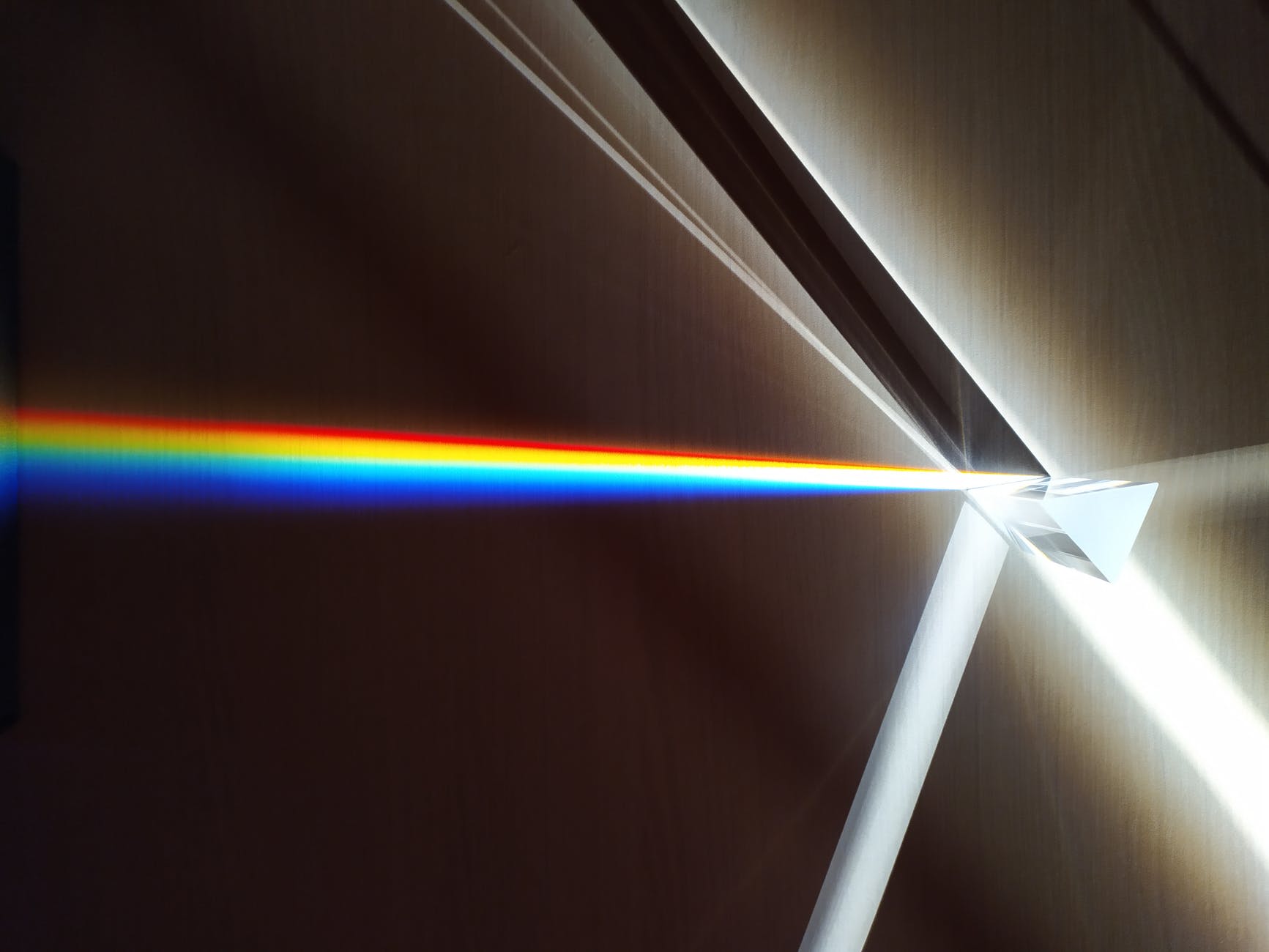

By my birthday, the gritty snow is receding. A tranche of mud and straggly grass is visible at the end of our small lawn. A layer of thick, glassy ice is melting the slowest, closest to the soil but holding hard over the promise of spring. I see it now, with the temperature creeping up, losing its hard edges and softening into curves, more a shield than a blade. I imagine water molecules intermingling as they cross the gradient of state, solid to liquid and sometimes back. I am fascinated with the idea of a thaw: this overlay of what has been frozen, flowing and mixing into an environment entirely new. These molecules are not just being released into the world that they used to inhabit, months ago in the fall. There is new growth, burgeoning beneath the surface. There is debris, blown in through storms and revealed on sunny days. All of it forms the slick of the mud beneath, around which these newly released rivers flow. How do I integrate parts of myself old and new? I am thawing from a lifetime’s accumulation of memories, thoughts, and beliefs that crystallized into a self. What do they create – freshly uncovered, perhaps newly seen in the light of compassion – in the fertile soil of my present life?

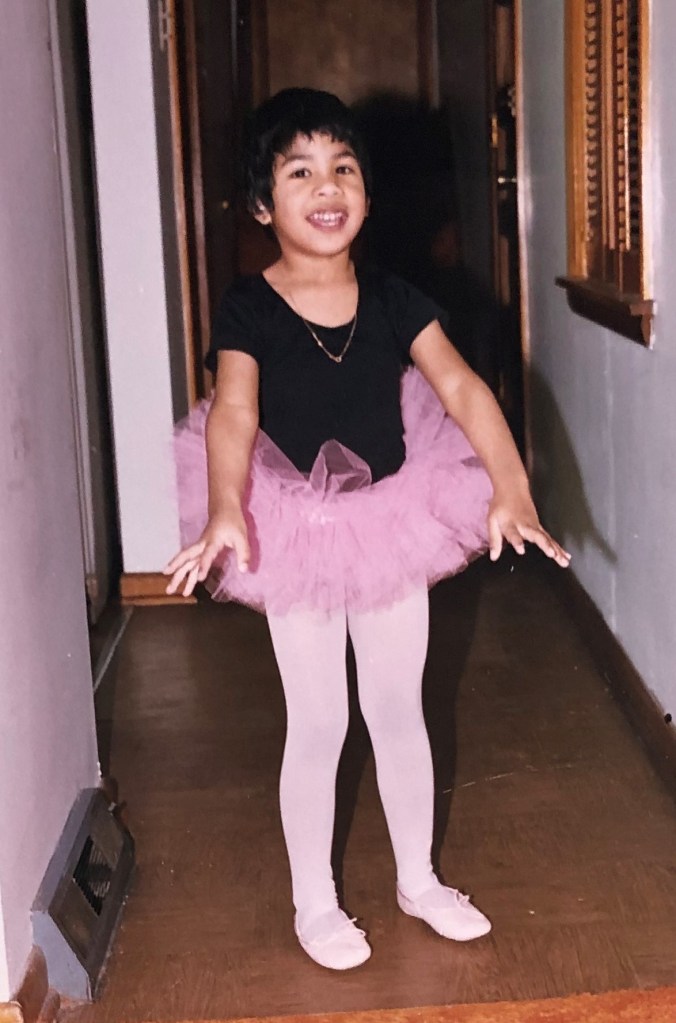

I am thawing a writer, who at six years old stapled together paper storybooks. Who kept a small journal, letters askew, noting her mother’s cancer diagnosis and the lies of a schoolyard friend. The girl who felt shyly elated as her fifth grade teacher told the school they’d see her name on the spine of a book one day. She lost a part of herself on the path to higher education, convinced she was duty-bound to set aside the arts. Who is she now? With a life dedicated to the field of healthcare, a body healing from chronic injury and pain? What does it mean to resuscitate the breath of life into that dream? To write, midlife, knowing a career may never come of it, is potency. It’s freedom.

To be forty-one is, to me, a penultimate age of sorts. I approach the year my mother’s life ended. I used to swim in a blackness around this thought. I couldn’t bring myself to picture a life beyond forty-two, as if I could avoid the pain of disappointment should I get sick and leave this world with unfinished love and work as she did. In Barcelona I became enamored of Antoni Gaudí. The Basílica de la Sagrada Família impressed me beyond my expectations; the architect’s vision, philosophy, and reverence for nature drew me in. I gasped upon reading that, after forty-three years* of working on the basilica, Gaudi was killed in a tram accident. Inessa immediately pursued with questions. “Why isn’t the church finished, Mommy? Why couldn’t the artist finish his art?”

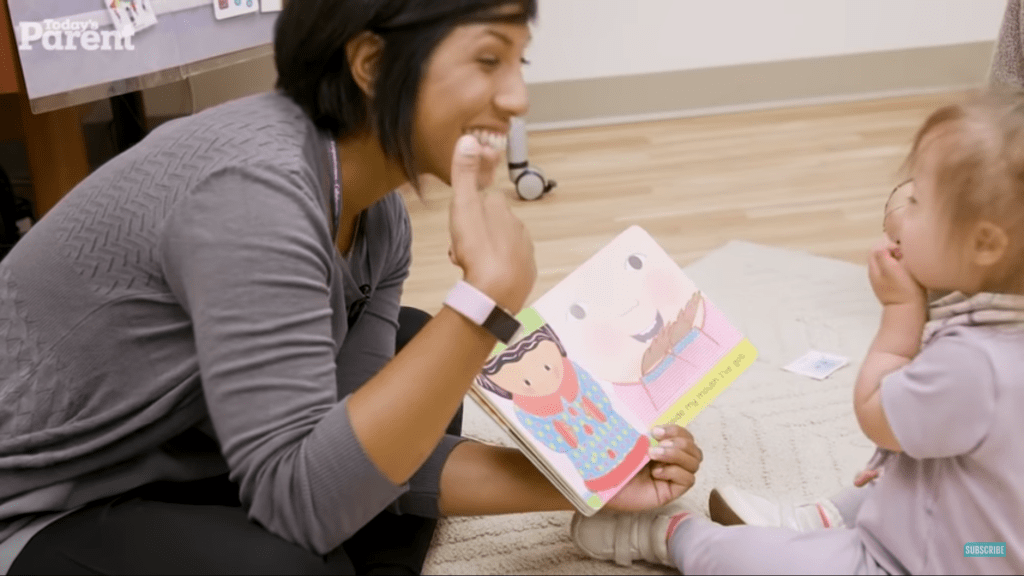

Sidebar 1: An unexpected challenge this trip was to find language digestible for the inquisitive 3.5, whose “why’s” proliferated beneath the statues of catholic liturgy. I landed on… “Mommy feels sad that the artist died by accident, before he could finish his art.”)

Sidebar 2: *imagine if it had been forty-two? How poetic for me.

At home, among souvenirs of inspiration, the thought brings me a measure of comfort. After all, it was Gaudí himself who said that he was not worried about the construction of the church extending beyond his lifetime, being influenced and shifted by the ideas of architects other than himself. He saw it as a testament to the ever-living and changing nature of faith, of God, of life. So perhaps I am projecting this pain of a shortened life onto him.

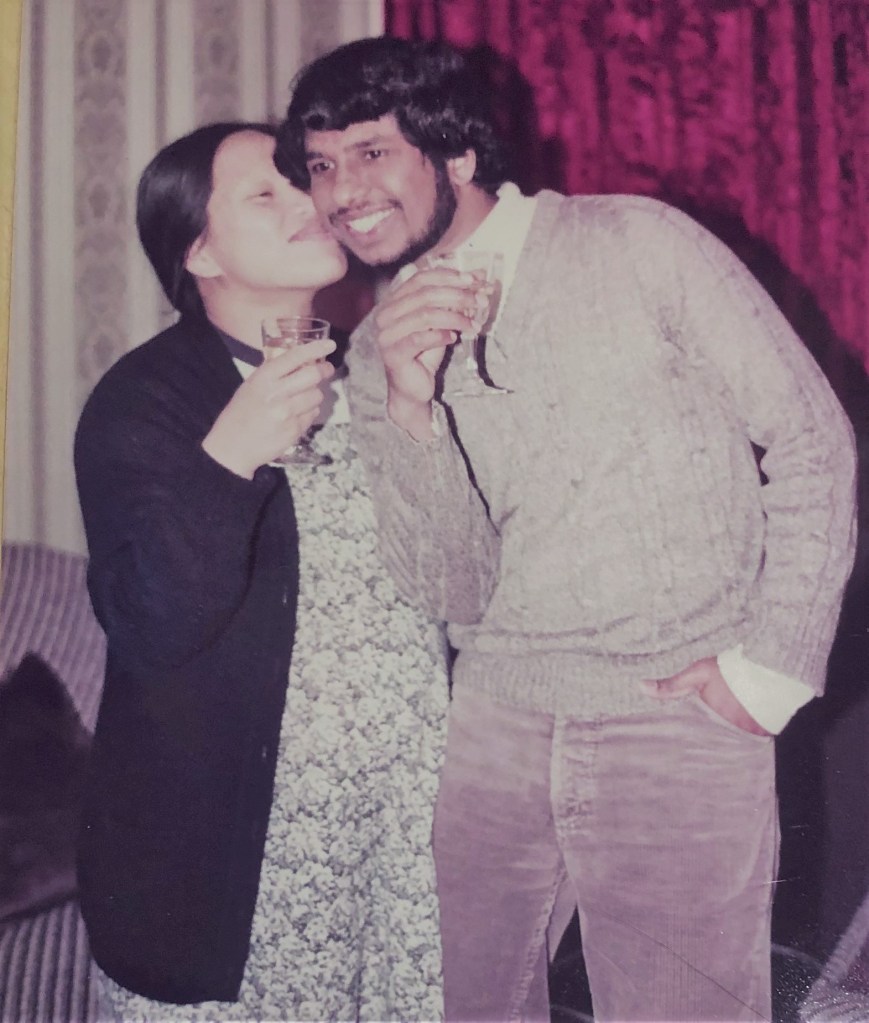

Similarly, I don’t know what my mother felt as she prepared for her own death, which included writing out meal plans for my father to keep her young daughters healthy, and making cassette tapes for us to know her voice when breath no longer sustained it. I don’t know if she was sad, or if her faith allowed her to move beyond this world with grace. I only know the pain of longing for her physical presence in my days. The ache of wishing for her to know me and understand me as only a mother can. The bittersweet rush of tears when a flamenco guitarist, demonstrating Eric Clapton’s preferred guitar, surprised us with a rendition of her favourite song, Tears from Heaven. I imagine that my mother felt the same overwhelm I do when I look at Inessa and imagine I could be separated from her without end. I don’t know. I will never know. Forty-two has always felt like a number too cruelly short for a life. And now, I’m only several hundred days away.

It feels different. Perhaps with this new life, built on the resurfacing of an old dream, that dread is melting into hope. Everything at forty-one feels fresh, like baby steps into an unknown world. At forty, I was still tethered to who I’d always been trying to be: a success, a leader in my career, a change-maker with something to prove. I was in a hurry, driven by fear of failure and forty-two, as if I could rest and reinvent myself in a prescribed amount of time; as if I were merely airborne between one trapeze and the next. I haven’t been airborne though. I have been composted into the soil. I am at the mercy and influence of the choler of winter, of the spring which will come in its time.

Barcelona’s artists wiped me clean. I took in wide-eyed the jeweled lightbox of Palau de la Música Catalana, built to lift the voices of Catalan factory workers in chorus, designed like a dazzling sunburst in a garden of glory. I marveled at the iterative experimentation of Picasso’s craft. He lived to seventy-three, and I hope that he didn’t feel unfinished, because I imagine each idea became a new lease on life. I swelled in the drumbeat of the flamenco performance, Inessa holding her ears yet persisting on the promise of an ice cream. I needed this trip now. I drank in the city’s love for its creatives. I found quiet balance meeting my little girl’s needs with afternoons in playgrounds, and slowly taking in art museums as she napped in her stroller. I was not in a hurry to be anything. I surrendered to the wonder of witness, allowing myself to … allow, myself.

I have always cherished my independence. In fact, I have prided myself on it in unhealthy ways, driving myself to do alone and to extreme what could have kept me connected to others. Grieve, alone. Lift, carry, traverse this world – alone. I love so many people. But I have kept in my heart a compartment, a space and distance in which I could hide in case of betrayal and disappointment. It is a space in which I could perversely comfort myself with the foreknowledge that I’d always been alone, so I could not be disappointed in others if they did not meet my needs. Something of this isolation is melting in me now as well. Inessa and I explored Barcelona by foot (and stroller), on a transit pass that took us from tram to bus to metro mostly with ease. Traveling with a stroller always gives me insight to the general accessibility of a place, firsthand experiences that highlight to me many disabling aspects of our public spaces. There were many moments in which I was tenderly grateful for strangers offering to help me carry the stroller up a flight of stairs, when the metro brought me to a station without an elevator (what would someone restricted to a mobility device even do?).

On one particular bus, carrying one other patron, I attempted to manoeuvre the stroller from the exit doors onto the curb; a gap, easily crossed with an able-bodied step, confounding to me with my sleeping child and stroller wheels. She dropped – with my heart and stomach – the wheels unable to cover the distance. They jammed for a moment in the slice of street between bus and curb. I gasped, and behind me, so did the gentleman also exiting at the stop. He helped me situate myself and the stroller safely, and I thanked him with profuse guilt and gratitude. But I was angry. Not with the city, or the bus manufacturers who could have made buses that lower or extend a ramp. Although that is true and worth advocating for, I allowed the anger to focus me on what I, in that very moment, could have done differently: I could have asked for help. Alongside anger was embarrassment. This kind stranger probably wondered what kind of mother I was, so hard-headed I gambled the peace of my daughter’s nap to try navigating the barrier on my own. Perhaps not. I know that criticism is my inner voice cloaked in the perceived judgment of others. But I allowed it. This resolute irritation with myself for not taking the easiest solution: asking for help.

I am not unlike so many others I know who are socialized with a deep, isolating, and arrogant fear of needing help. I felt it intensely during the year I worked at the hospital. I needed help, as a sleepless parent of a toddler who was frequently home sick from daycare. I needed help, because I was drowning in the workload of a system fuelled by urgency, scarcity, competition (capitalism). I needed time, space, recognition for the pain in my body that swelled and spiked, the depression trying to tell me I was in the wrong place, the anxiety that was flooding my system with cortisol and burning me up from the inside out. But I struggled with voicing these needs, convinced it was me that was somehow defective.

On the one hand, I can say yes, I needed those around me and the entire work culture to see my needs and recognize how deeply damaging it was to me and to others chewed up by its expectations. In fact, my work on the hospital’s accessibility file directly fought for this recognition. I saw my role as an advocate, before I began to see how I might be part of the 27% of the population that have a disability. I had only suspected my neurodivergence, but looking back now, I see how part of my struggle was being an ADHD peg in a neurotypical pegboard. I recognize the impact of my pain – chronic, fluctuating, invisible – as experiences common in the disabled community. There is humility and comfort as I accept my body, with its pain and need, knowing that it brings me belonging to a vast, strong and intelligent community of people the world over, who have existed and persisted since the beginning of humanity. Thawing this identity has meant allowing my narrow valuing of myself for my capabilities, my independence, my achievement of the societal ideal, to expand.

I have needs. It feels revolutionary to even allow myself this gift. I need hours a day to give my body the movement and therapy it needs to heal. I need to work in a way that keeps my brain chemistry in check. I need to recover from a lifetime of damage wrought by beliefs and ambitions I did not know better than to wield. This means rest. And asking for help.

I did so, with love. On every bus trip after that drop to the curb, I made eye contact, and with confidence and trust, I gestured with my haphazard Spanish to ask someone to help me manage the stroller. I used my voice to politely ask people to move so I could use the accessible/stroller spaces; I drew people from their phones and isolation to ask them to collaborate with me. I know some were disconcerted. I threw them for a loop. But I know I also made their day better. Why not? What is it to help someone? To connect with a fellow traveler, to be slightly inconvenienced so that I could also make my way through their city?

I think the freedom and joy it gave me to ask for help was rooted in knowing that I belonged. Yes, I was visiting as a tourist, but Barcelona welcomes its visitors – come, see our buildings, taste our foods, let your heart be filled with the beating pulse of this place we love so much. I belonged because I let my heart be filled, and in turn love a place so brimming with life. I belonged, no matter how I could move around, no matter what I needed, and I think it is only now with the heart of an artist I can believe this and ask for help. In the same manner, I explained to the guitarist my heartbreak and joy to hear Tears from Heaven that day. To share my love, pain, grief, need – to connect, and be changed.

To be disabled is to be human. To live, ability notwithstanding, is to age; to age, a gift. To be here, a spirit in bodily form, a miracle. All the learning and eye-opening that I’ve been gifted through the disabled community (clients, colleagues, authors and advocates), has turned the soil that nurtures my self-acceptance. Asking for help, trusting and demanding that I be woven into the fabric of their city and their day, gave me access to a deep well of joy in humanity. I know that I bear incredible privilege in having a body and countenance that appear within the norms of accepted human variation; a keen sense of all the ways I “pass” on colonial terms. I can navigate the world with more ease and acceptance than can the vast majority of folks who identify as disabled. What I hope I can do, in this practice of asking for help and recognising the innate humanity of having needs, is my (tiny) part to dismantle ableism. I hope I can inspire a small measure of collective responsibility, and joy in subverting convenience, speed and independence for connection – especially in folks who never have to think about how they get through their days.

This acknowledgement of my own suffering is another floe that’s dissolving. Frozen long ago, without knowing, was my ability to grieve; to see my pain as legitimate and allowed. It is old enough to bear its own children. It has taken me so many spears, so many angles, to reach this deep part of myself, as the pain has locked itself within layer after layer – perfectionism, self-denial, overwork, achievement, people-pleasing and isolation, to name a few. To understand the impact of all these poisons on my body, is to see the sediment tarnish the spring melt – to see oil curling into the water and seeping into the soil. I grieve now. I cry out the pain in my joints. I forced the strangled voice of my past into the cold air as I surrendered to the frigid waters of lake Ontario. I pray the earth can hold all this mess. I give over to trust, that the waves will take my grief and leave me lighter with every day that I let my pain be known. I cannot be the girl I was, and hope to progress untarnished, even as I let these moments come undone after so long. I do not unfreeze into a child, but a woman with a child. I become something else altogether.

I learned that a lovely man named Matt built the sauna by the lake as an experiment, a hobby project hitched to the back of his truck. Hoping to inspire residents to get out to the waterfront, underutilized in winter, he showed up every Saturday to offer a space for the community to enjoy. Pay what you can, swim or no swim, share a space with your neighbours. As I nestled knee to knee, strangers shifted and chatted and held an invisible web. People would go in and out, some to the lake, or to breathe in the rain-flecked air, or just to allow someone else a turn in the crisp cedar heat. Although I had imagined myself performing this ritual on my own, I was drawn into their arms, celebrated for my bravery, and assured they wouldn’t let me attempt this feat alone. For safety, for love; whatever the case, I am glad my heart is soft enough now to have graciously accepted. I laughed and made friends, screamed and whooped at the glacial embrace of the water. I sent my crying heart into the waves, the vastness essentially a sea, witnessed and welcomed by beautiful weirdos just like me.

I feel baptized. I feel new. I feel scrubbed and scraped and bewildered by my luck, the immensity of my life a gift; a breath from naught to full. A part of me imagines that every day beyond forty-two will feel this precious, that I will live in holy gratitude. And then I remember that no day is promised; if I am granted enough life to reach forty-two, it will be no achievement. I can only lay each day I’ve lived on the altar of my life, grateful for the stones and salt and returning scent of spring. I am forty-one.